Aida Osman Is A Muva!!!

When Aida Osman was thirteen she worked in the cornfields of Lincoln, Nebraska. It’s a fact only mentioned once, off-handedly, in a profile by Forbes, but one I felt demanded further explanation.

“It’s kind of predatory. Like, these different farms go to the middle schools, and they set up a booth, kind of like the army reserves or the Marines,” she detailed to me. “Essentially, it’s rush week at your middle school, but it’s like, which local farm are you going to give your [child] labor to?”

It was a memorable and formative experience for her, though. She made two thousand dollars from it—“Bro, that’s not all right. That’s not a safe amount of money to give to a young child … I bought drugs, like, the next month.”—and it was the first job she ever held, a fact that makes her reflect on her current phase in life.

“This is the longest stretch of my life I haven’t had a job, to be honest, because I’ve gotten pregnant, and I just got married, and I decided to take a break, you know? And it’s been amazing, but I’ve definitely had to put my value in other things like, I don’t know, being a mother. I don’t know, having a family. But I’ve always defined myself as being a worker,” she says.

Her résumé would certainly stand to support that view. At just 28, she’s written and performed in an unimaginably wide variety of comedic entertainment. A few shining standouts are Big Mouth, Wild ‘n Out, Group Therapy, Crooked Media’s Keep It, Betty, and, most recently, Issa Rae’s Rap Sh!t. She bears the mark, too, of someone who’s spent more than their fair share in comedy writing rooms. I entered the call irrationally nervous that somehow I wouldn’t be professional enough, but was quickly disarmed by her tendency and ability to rattle off brilliant, irreverent jokes and eclectic cultural references at breakneck speed. A new fear, then, very quickly took hold—that I wouldn’t be funny, or cool enough.

Her craziest job yet, though, she says, is motherhood, a role of which she was only eleven days into at the time of our conversation— “Bro, this shit is so new it flashes in front of the screen like in a zombie movie. It’s like, DAY ELEVEN, and then you find me, and I’m under a bunker, breastfeeding an infant,” she quips.

“There’s no other place of employment where you’ll get shit on, spit up on, and also cuddled with, and you don’t file an incident report on that nigga.”

Amidst the bites, cries, and charms of a, “young, silly little girl,” Osman was generous enough to speak with me for Lil’ Mama about, in the same breath, David Foster Wallace and motherhood (“Saheim, you’ve never had to talk to somebody about philosophers with a titty in somebody’s mouth”), how African people have always been connected to music and “Gen Alpha niggas” who wear Balenciaga boots but can’t hold a conversation, and, of course, more generally, Black culture and comedy.

You’re from Lincoln, Nebraska. You’ve spoken about how growing up, you often felt “weird and lonely,” and a bit isolated from Black Culture. You said [to Teen Vogue], “It's the reason I had to look up every song by TLC, SWV, and Mobb Deep. I had to find Black culture, and then hold it very dearly because it wasn't always accessible to me. I built my own attachment to it.” I’m very curious, what did that Black cultural education look like for you? How did you design your curriculum, so to speak? When you say “you had to find Black culture,” where did you look? And, what did you find?

I mean, even now, I still feel like I’m studying Black culture because I come from an African household. You know, my mom didn’t have that built in. My mom’s deepest reach into Black culture was, sometimes she’d play Prince songs in the crib, and then make fun of that nigga for being gay.

According to Osman, it was in college, when she finally got away from her predominantly White high school, and started to date Black people, that she began to learn about Black culture.

I remember the first date I went on, this guy showed me The Wood (1999), and after I told him “I’ve never seen this,” he was like, “What? I’ve seen this six hundred times with my mom. She won’t stop playing this.” And then he just showed me every movie that was directed by Rick Famuyiwa.

Then he showed me Brown Sugar (2002). And we just went down this hole where he was like, okay, we gotta show you every Sanaa Lathan, we gotta watch Love and Basketball, and then we gotta watch every Taye Diggs movie, and oh! Do you know that Mos Def has this album? Have you heard The Panties by Mos Def?

I’ve been lucky to have people who have really been liaisons into it, and have been super patient with me, who’ve almost found it endearing that I’ve been like, “I’ve never seen Friday (1995),” and I’m, like, twenty-two years old with a whole job.

Osman’s initial foray into comedy writing was actually through writing satire. She tried writing for her college’s satirical newspaper, the DailyER, and even The Onion, but found that neither really understood or embraced the kind of humor she was attempting. I’ve had similar experiences, and it’s, in fact, one of the primary reasons I started Lil’ Mama.

It wasn’t until she tried stand-up, and a tragedy occurred in her family, she says, that she feels comedy truly began to become an undeniable part of her being.

When did you start doing stand-up?

I did it one time when I was nineteen, and I didn’t love it. I was really scared, and I think I just read a bunch of one liners out of a big notebook. I brought a huge notebook on stage. I remember one joke, very specifically, was like, “Here’s my impression of a girl who doesn’t understand the severity of the Holocaust— ‘Oh my God, did you use my toothbrush last night? What are you, fucking Hitler?’” and that was the only one that got even half of a laugh and I was like, “Oh shit, I’m kind of bad at this.”

So I quit, but I kept writing. And even recently I found a bunch of old journal entries from when I was a kid where I was writing letters to friends and I was like, “Hey girl, what’s the deal with Yogos? Have you seen the Yogos commercial? It’s like yogurt balls, super weird, huh?” And [so], I was writing as a standup even when I was younger in my journal entries, but I didn’t realize then. But I know now, like that’s set-up, premise, punchline, tagline, whatever. But it was kind of always in me to think that way.

My brother passing away, as tragic as it was, was weirdly a huge part in my comedy journey, because I didn’t start doing comedy until Sam died. [He] died in 2017, and that’s the magic about comedy— you do it because you need it. Like, I never thought this shit would get me on a television show, or get me to write for TV, or anything. I was just sad, bro. I just needed something. I needed my life to be either full of thinking about funny things or trying to find funny people. So, that’s what I did.

And I sincerely have not stopped since then, except for COVID. And even then I did some shows out of trucks. I did some shows out of the flatbeds of trucks, and I just did some shows seven months pregnant. It’s really hard for me to stop. Stand-up will always be a part of my life, and the core thing that anchors me. If I don’t do stand-up I start to get really, really stir-crazy, to be honest. Right now I haven’t done stand-up since I was maybe seven months pregnant, so it’s been two months? Whew! I’m starting to feel like I don’t know myself.

You graduated from the University of Lincoln-Nebraska, in 2018, with a degree in philosophy. What made you pursue that major?

I probably was just doing too much acid in college, to be honest.

Oh, okay.

No, I discovered Cornel West when I was pretty young. Maybe eighteen years old. And I just felt like it was the first time my ideas were reflected back to me by somebody who spoke with so much eloquence, and I had never heard someone speak like that. I still, to this day, if I ever want to do a speech or need to be persuasive in any way, I’ll go watch Cornel West talk. There’s something about the cadence, there’s something about the melody. He’s just so good at thinking and speaking at the same time, and he’s a philosopher by title.

He’s not a “creative”. He’s not a “content creator”. He’s, like, an old school philosopher, and we don’t have a lot of people who will shamelessly call themselves that anymore. I like that.

I love to ask people what their “old job” would be, ‘cause shit clears up real quick. Because nobody’s gonna be like, “Yeah, I would prop up a phone and do little dances and try to get a brand deal for energy drinks.” People start to go, “Damn, well, I like kids, so I’d probably be running a nursery.”

I still think, to this day, my [old] job would be sitting up somewhere with a bunch of men and women, and talking about problems, and things that we think.

Yeah, I feel like that was probably the best deal back then.

You definitely had to earn it, though, right? Like, now our philosophers are like—who’s that guy who died? Who was doing all that Black love stuff?

Oh, Kevin Samuels.

Yeah, now people can claim to be self-actualized, and they can take on the name of “philosopher,” but they’re some of the dumbest niggas in the world.

There’s another philosopher named A. A. Rashid, who I got put on to by my husband [rapper Earl Sweatshirt], and he’s just studying the telekinetics of Blackness, and like the ancestral telepathy of Black people, and he’s proving it. He’s demonstrating his research. And, you know, people are quick to call stuff “woo-woo,” but people are also quick to hate Black people, so I know they’re wrong.

Do you think there’s a funniest philosopher?

Bro, I’m reading [Consider the Lobster] by David Foster Wallace right now. He’s one of my favorite people. You know how Gen Z humor just leans so ironic, and then it became so meta that it was a joke, on a joke, on a joke, on a joke, and now we don’t even know what we’re saying, and we sound like aliens to the adults around us?

Right.

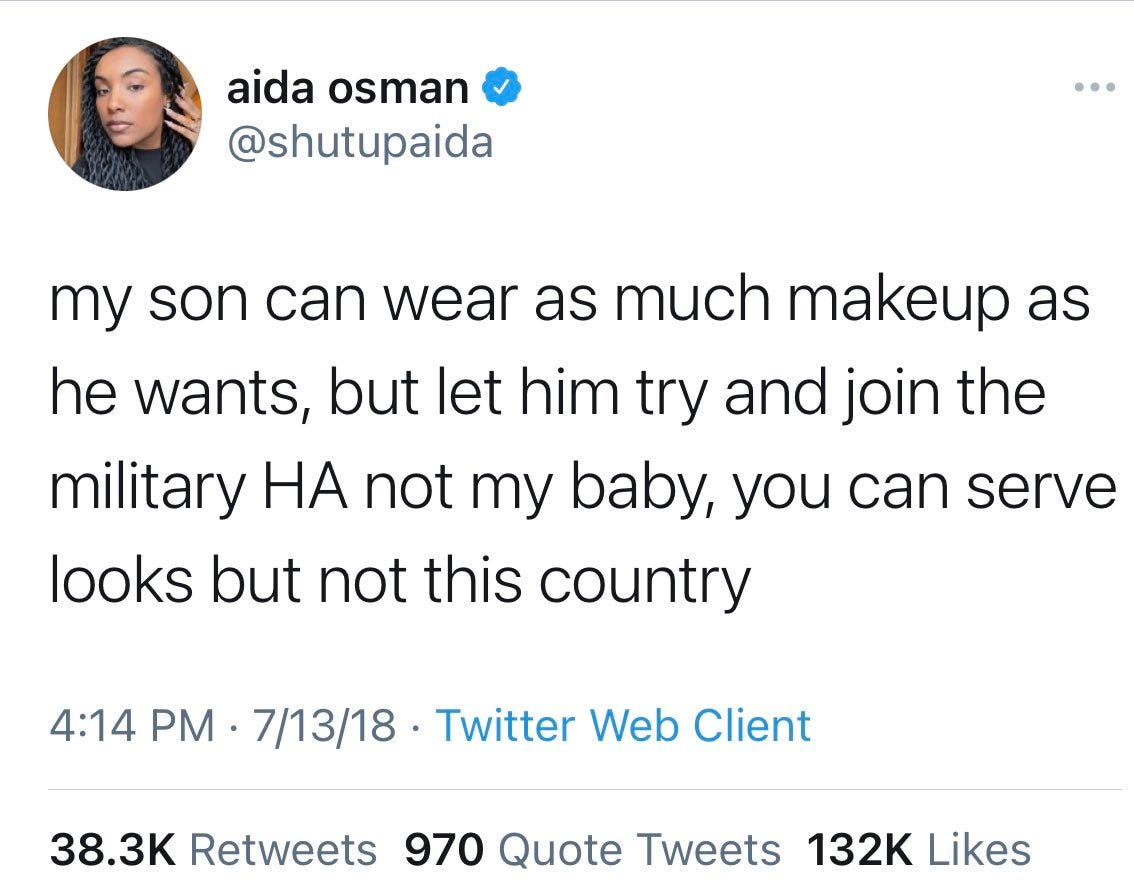

So, there’s this wave of artists and creators that are operating under this moniker that’s been [termed] New Sincerity. And it’ll be someone like Zadie Smith or David Foster Wallace, and these people who kind of steer away from irony. I would even say that at their best, they’re steering away from it, and at their strongest, they’re rebuking it. It’s all about embracing the cringe parts, and I just can’t do it with these Gen Alpha [niggas]. They fear everything, and everything is cringe, but they all somehow have Balenciaga boots. Like, they’re all wearing this uniform of “cool”, and then when you talk to these niggas they can’t even make eye contact for very long.

Yeah. What’d you ask me? Funny. David Foster Wallace. Yeah, I’m reading Consider the Lobster right now. He also wrote Infinite Jest, which I’ve literally never been able to get through ever in my life, but I like these essays.

He opens up and he’s already talking about how the annual AVN Awards are so much more fascinating than the Oscars. He writes with such a sharp tongue, and I really like people who don’t always write to be easily understood, if that makes sense.

(Referring to an earlier comment I made about the density of Earl Sweatshirt’s lyrics) You even mentioned it with my husband. I really appreciate that everything is kind of imbued with a challenge. Like, oh, go look that up nigga! Go put that in Google, or ChatGPT, or whatever the hell you use now as your second brain. Go figure it out. It’s kind of a trickster archetype. It’s like a troll under a bridge, but he’s not trolling you. He has secret knowledge.

I want to talk a bit about the connection between music and comedy. You’ve talked about being involved in musical theatre growing up. You were also on a show that very prominently featured music [with ‘Rap Sh!t’]. I know that in my own writing, music is very important. And when I think about Black Comedy, it feels like music has always been a part of that deep cultural well that we pull from, and that can really make the difference between whether a piece of comedy is just comedy or “Black Comedy”. Have you seen The Original Kings of Comedy?

Yeah, for sure.

Okay, there’s a scene in that where, and it can just be that Steve Harvey is bad at stand-up, but there’s a scene in that where he does a set with absolutely no set-up or punchlines, but instead just plays, like, a bunch of songs from the 1970s. But he’s still, by all metrics, killing. And I think something like that really only works with Black culture. Like, I can’t imagine John Mulaney going up on stage and just playing Neil Diamond for five minutes, and getting a similar reaction, you know?

You know, Black people, as complicated as we like to act, there is a beautiful simplicity to us. Which is that across all African cultures, there is some type of stomp dance, some type of clapping dance, some type of rite of passage where you’ve got to prove that you’ve got the spirit of music in you in some way, and I don’t think that that has ever gone away in us or ever will. And I think it looks like we be having more fun than everybody else, but I think we just have access to it. And we’re not afraid to access it.

And, now, is Steve Harvey bad at stand-up? For sure. For sure, he’s bad at stand-up.

[But], I think that people like to feel that they’re a part of something, and sometimes that’s why referential humor is so popular—kind of cheap, even, sometimes. Because you’re just like, “Hey, remember when this happened? And people are just like yeah!!!! I do!!! Yes!!!!” and they pee themselves and they clap.

Right.

I think that music is some of the easiest referential humor, and also the most potent. Like, that shit really goes in. That’s why you remember lyrics from when you were eight.

Throughout our conversation, I’d bring up various comedians who reminded me of something being talked about, and, pretty much every time, she knew them. On one instance, this led to a wider conversation on the Black alternative comedy scene, and her love for the craft.

Have you seen Devon Walker’s new podcast, My Favorite Lyrics?

Oh, yeah. You know, the Black alternative comedy circle is so small. If they’re good, I know them. You know? If they’re working, I know them. Honestly, let’s just say that if they’re funny, I know them. Even the new ones, I try to be tapped into who’s funny at eighteen, nineteen—bro, I know you, you know what I mean?

I think that’s just my love of the craft. It’s an obsession. I really hate talking about it sometimes, like I’m jinxing it or something, but I just love comedy so much.

I can’t stop looking. And when you can’t stop looking, you can’t stop finding. So.

Speaking of the Black alternative comedy scene, I think that’s kind of the niche I discovered you in, which was, at that time, primarily on Twitter. You know, when I think of that time, I think of you, Ayo Edebiri (since deactivated) was big on there, Zack Fox, Yedoyé Travis, etcetera. You all seemed to be bridging the gap between the weird, alternative comedy that I was embarrassed to share with my friends, like Adult Swim or Mr. Show or Tim Robinson, with traditional Black comedy and cultural tropes, which remains very influential on me [and Lil’ Mama].

Bro, Saheim, it’s so weird that you say that, because when you’re a part of a “movement” or a thing that’s happening, you don’t know that you’re a part of it.

You’re just tweeting, or you’re just making jokes. You never know when you’re a part of a large group of people that are accomplishing a thing, or making a wave. I didn’t know that was happening. I think I just liked Jaboukie [White-Young] a lot, and I saw how he managed to write for shows just off the internet.

I was [also] still in college trying to figure out what I wanted to do. I was pre-law, and I went to do an internship with the public defender’s office, and I hated every second of it. Like, these people were so boring. Their lives were chaotic. They got paid very little money. They were servants of the state, and they were great people, but they hated life and they hated their jobs. They were overworked. And I just seemed less and less excited about learning the penal codes, and torts, and the laws of this country.

And even though some public defenders are really noble people and are trying to help people game the system and all that, they just seemed boring as hell. So, I was trying to find a different career path.

What are your thoughts on what Twitter has become—how it was once a place where comedians could really be discovered, and now it’s.. whatever it is now?

Well, I hate to act like the Last of the Mohicans, and as if it’s all over now, but it felt like the spheres of influence were so much smaller back then. I don’t think you can get discovered off of Twitter anymore.

I think you can still get discovered off of TikTok, which I’ve watched happen recently, even. But there’s not as simple a pipeline from the internet to industry-work. Specifically, in film and television, which is what I was geeked on my whole life, it didn’t seem like there was a pipeline unless you did stand-up or something, which I felt like producers respected, and you had a decent following on Twitter. It just felt like that’s all there was.

Maybe I have some blind spots, but I feel like you don’t get on TikTok and become a TV writer. But I might not be tapped in anymore, lowkey.

Yeah. You know, while Twitter is not what it used to be for young, aspiring comedians, I think younger comedians are still, irregardless, using the internet to share their comedy and really try to start a career. There’s this kid I really like named Asad Benbow, have you heard of him?

Oh my god, Asad—bro. Like I said, you and I are gonna be kindred spirits. If we like the same stuff, we’re gonna like the same people. That’s what I’ve found. And Asad, when I was saying “if they’re funny and they’re good, I know them,” it’s because I have a hole in me, and it’s the one that needs to laugh, and needs to be inspired by the people around me. And when I found Asad, I was like, oh, the kids are okay. I mean, sure, the kids are neurodivergent, but they’re okay. You know?

So, Asad’s great. Asad’s great. I be thinking about him when I write scripts. He’s such a good character. I really want to see him in television shows. He’s one of the funniest young comedians in the New York scene right now.

I thought about him when you were talking about how Gen Z and Gen Alpha are so irony-pilled right now. I feel like he does a really good job of blending that ironic Internet humor with sincerity and the traditional tropes of stand-up.

Yeah, I agree with you. You know what’s cool about Asad? He’s actually cut from the cloth of the people he’s making fun of. He’s not an outsider. Like, he’s a standup comedian who is chronically online, will show you some of the rarest rappers who have, like, five, six listeners, he’s a huge music fan, he went to fashion school, like, bro, he’s not punching down. He’s punching across if that makes sense? He’s making fun of himself, and I think that comes with vulnerability and sincerity, which is already fun and funny, and then once you’re of a culture, you know how to make fun of it. You’re just the best at making fun of it, ‘cause it’s a love letter to it.

Also, everyone’s a nerd. All of the people—me, you, Zack [Fox], Ayo [Edebiri]—all of these people, they love this shit so much. They’re funny in real life. They work hard to be funny. They know how important it is to surround yourself with funny people and to constantly be controlling your input so that you produce funny stuff. Like, I don’t know, bro, you gotta have some literacy in life! And it’s really cool to see all the comedians that I love and respect and have come up with, and now can call my very close friends—they’re all the smartest people that I know.

Would you say you have a generally positive outlook on the future of the industry?

I do. I think a lot of us have been scared away recently by the difficulties of excelling or succeeding in our industry. And, there was a time when if you were a comedy writer, you were making, like, millions of dollars a year. I’m talking Family Guy era of TV. When TV was more scarce, there was an ability to really change your life off of this career path.

And, I think now you’ll find some of the most successful comedians you know are still living gig-to-gig, paycheck-to-paycheck. [But], as long as that desire is there, and that love is there, we’re gonna be okay. We’re all gonna be okay. Maybe it’s harder to get shows picked up, maybe it’s harder to break through in the ways that you want to, but you just gotta keep working, and loving the work.

The industry is an afterthought. The work is the primary thought. How it succeeds, how it fails, how much money you get from that, all of it is arbitrary and secondary and just not even something that I can concern myself with, to be honest. If they want it, they want it. If they don’t, they’re missing out, or whatever. The industry is not them, it’s us. They need us. They operate fully on us feeling galvanized to make stuff.

That’s why I’ma gas you every time! Like, yes, the content is amazing. What you do is amazing. But mostly, your follow-through. I’ma start sounding like a pastor, but, that’s what they don’t want you to have, which is the ability to finish something. They want you to feel so scared and so confused that you don’t even finish. That you instill so much self-doubt in yourself that you don’t even make it to the finish line. So, the fact that you’ve finished something, you won. I keep it that simple. If I finished, I won. That’s it.

We’re always gonna be okay.

Aida Osman recommends:

- Nelly & Ashanti: We Belong Together “Tell people to watch my new show. I didn’t write on it. I’m not in it. That’s just my new shit.”

- Gayle King’s Instagram “I’m really, really, really deep into that. That neural network that she’s built out for the world. I might do an Off-Broadway show where I’m just doing Gayle King’s life story. I have a strong parasocial relationship with Gayle King.”

- For smart people to have babies. “Smart niggas need to populate the earth. We gotta stop letting dumb people have so many babies. So, if you feel like you got that shit, you need to have a baby. If you feel like you’re really up to some good, have a baby. We can’t fuck around anymore.”

- To look at Ludacris’ beard next to Seneca Crane’s.

Lovely interview

I'm waiting patiently for her to start her own Substack cause I know it would be great ❤️